“I work to create a cosmopolitan world and a nomenclature of “philosophy” that means the pursuit of ways of well-being, conviviality, and modes of imagining instead of pursuing that non-existing queer property: wisdom. Dualism is false both in the sense that consciousness exists separate from embodied existence and in the sense that there is a sphere of mysteriously lodged prescient knowledge accessible through superior reason or intuition by the privileged.”

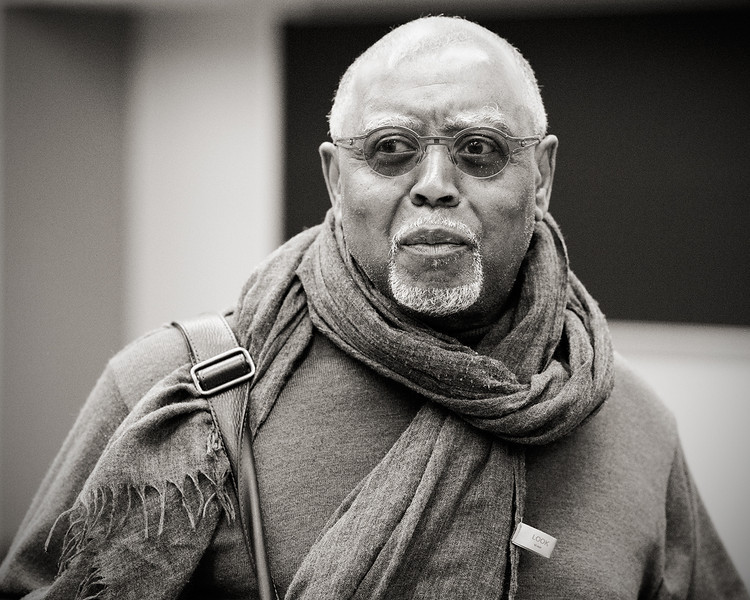

Leonard Harris

Leonard Harris

Leonard Harris

Leonard Harris is the Joyce and Edward E. Brewer Chair in Applied Ethics at Purdue University. He is the editor of Philosophy Born of Struggle: Anthology of Afro-American Philosophy From 1917 (1983/2022), editor of The Philosophy of Alain Locke: Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (1989), co-author of Alain L. Locke: The Biography of a Philosopher (2010) and coeditor of Philosophic Values and World Citizenship: Locke to Obama and Beyond (2010). Many of his essays were recently collected in A Philosophy of Struggle: The Leonard Harris Reader (2020). He is a recipient of the Caribbean Philosophical Association’s Franz Fanon Lifetime Achievement Award and SAAP’s Herbert Schneider Award

What does American philosophy mean to you?

I am a destroyer of the womb within which I was nurtured. I was educated in schools that prized America as a magnanimous nation. These same schools touted the undue status marker “philosophy” as a discipline and way of life pursuing wisdom through its truncated reasoning methods. “American philosophy” has a family of meanings, statuses, and descriptors that I want to change.

Pragmatism, with its rejection of absolutism, arguments in favor of seeing “truth” as a product of our doing and discovery through especially methods of intelligence and laudable promotion of pluralism is only one of America’s products. Other products include American scientific racism, racialism (black, white legal census categories), “gun” rights (understood as a God-given, naturally good, intrinsically warranted or necessary as a condition for social life).

The American character is often described as entrepreneurial and sustained by compassionate but rugged individualism. “America” also means American schadenfreude, draconian sources of self-worth and status achieved by torturing, and the unmitigated greed well described in Stanley Nelson’s Devils Walking: Klan Murders Along the Mississippi in the 1960s, David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon, Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers’ They Were Her Property, and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese’s Within the Plantation Household. So much for meliorism. So there are limited benefits to methods of intelligence and the usefulness of instrumental reason: rarely if ever are abolitionist movements successful, but such movements (like slave abolition of every kind) should be tried despite nearly assured failure.

I work to create a cosmopolitan world and a nomenclature of “philosophy” that means the pursuit of ways of well-being, conviviality, and modes of imagining instead of pursuing that non-existing queer property: wisdom. Dualism is false both in the sense that consciousness exists separate from embodied existence and in the sense that there is a sphere of mysteriously lodged prescient knowledge accessible through superior reason or intuition by the privileged.

American philosophy would then mean contributions by members of a laudable community.

How did you become an American philosopher?

I was an experiment. Francis Thomas, the only teacher of philosophy at my undergraduate school, Central State University, in Wilberforce, Ohio, came to my dormitory room when I was a senior in 1969. He took me to his office and told me that “Miami University has a spot for a Negro to attend graduate school in philosophy. You will go.” Robert Harris, Chair of the Philosophy Department at Miami had called Thomas and told him to choose a Negro to receive a Teaching Assistantship, for an M.A. degree, because they were willing to try to see if a Negro could do the program. Thomas chose me.

I had no idea where Miami was located (Miami, Ohio) or what graduate school was. I just loved philosophy and was good at it. When Thomas called me down from my dormitory room and bade me follow him, I was scared that I was going to get put out of school for being a confused black radical poetry-publishing hippie. I just agreed to whatever Thomas said and signed wherever he said. Then I attacked the challenge. Some of my days at Miami are chronicled in a forthcoming documentary about protest against the Vietnam war and racism (Bittersweet: Black College Life at a Predominantly White University); I finished my M.A. in a year and went to Cornell University, finishing in four years. After being repeatedly interviewed for teaching positions in philosophy and being told, as I was at Northwestern University in 1974, that they only needed to interview me to satisfy diversity requirements but certainly would not need a Negro, I stopped. My first job after Cornell was at Central State University as an administrator.

My interest in pragmatism began with my research on the philosophy of Alain Locke in 1982 in the archives of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. I discovered a founding member of pragmatism that was only discussed as a Negro promoting Negro culture, not as a philosopher with a large body of published works informing the cultural formation of the Harlem Renaissance. From the publication of Philosophy Born of StruggIe (1983) I have been able to promote the study of Locke’s philosophy, African American Philosophy and Africana philosophy.

How would you describe your current research?

Promoting public philosophy and the version of philosophy I defend through leonardharris.net, oxfordpublicphilosophy.com and oxfordpublicphilosophy.com/insurrectionist-ethics.

I am reading books to help me finalize a presentation and defense of “Philosophy Born of Struggle” within the context of “The Nature of Philosophy.” I hope to further develop the concepts of necro-being, which means living as if you were dead, as if your life doesn’t matter at all, as if you’re not even there. I’m also developing concepts of anabsolute, insurrectionist ethics, non-moral universe as moral verse (not a moral universe), dignity as efficacious agency, seeing the unborn, critical pragmatism and rejection of conceptual monsters of unified selves, persons as reasoning machines, and pessimism despite the non-existence of a human teleology. I am relying on Arabic, Chinese, Indian, African, Hispanic and classical resources.

A book entitled What is Philosophy? was, if not the last book, nearly the last book, written by José Ortega y Gasset, Giorgio Agamben, Martin Heidegger and Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari. I suspect that will be the title of my last book.

What do you do when you’re not doing American philosophy?

Hang out with my friends and family. I ride with my bicycle club, the Wabash River Cycle Club, or go on rides usually sponsored by a Major Taylor Bike club in Florida, Georgia or North Carolina. I am a “D” rider (12-15 miles per hour, for usually 30 miles a ride) and when I am at my best, I am a “C” rider (15-18 miles per hour for 30 to 40 miles per ride).

What’s your favorite work in American philosophy? What should we all be reading?

Favorite work: David Walker: Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles, to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1830)

What we should be reading:

- Alain Locke: The Philosophy of Alain Locke

- Corey L. Barnes: Alain Locke on the Theoretical Foundations for a Just and Successful Peace

- Harriet A. Washington: Medical Apartheid

- Dorothy Roberts: Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-first Century

- Katie Mack: The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking)

- Lee A. McBride, III: Ethics and Insurrection: A Pragmatism for the Oppressed

- Jacoby Carter & Darryl Scriven, eds.: Insurrectionist Ethics: Radical Perspectives on Social Justice

- Andrea J. Pitts: “The Polymorphism of Necro-Being: Examining Racism and Ableism through the Writings of Leonard Harris,” The Journal of Philosophy of Disability

- Shelley Tremain: Foucault and Feminist Philosophy of Disability

- Lewis Carroll: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland read against Jane Addams: Democracy and Social Ethics

- Sun Tzu: The Art of War read against H.D. Thoreau: Walden

- Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali: The Incoherence of the Philosophers and Averroës (Ibn Rushd): The Incoherence of the Incoherence (both absolutists that disagreed on whether reason was a route to viable wisdom) read against James’ or Dewey’s view of reason and Maya Angelou: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings